Reviewed - The

Reviewed - Curio Shop by Eric S. Anderson

Curio Shop

Let's talk about Surrealism. Not Dali, Man Ray, Kahlo. or Ernst, but more filmmakers like Buñel or Artaud or… well, Man Ray. Huh. I didn't see that one coming. Surrealist film, that branch of cinematic expression that attaches to the dream-like state of non-reality while still existing in a realm of possibilities, has many forms. Easily my favorite takes the form of black comedy, often combining elements of fantasy or science fiction with an avant grade sensibility. This is the milieu that the film Curio Shop inhabits, and one of the reasons you should seek it out.

The story of Curio Shop is described as a "Post-Apocalyptic Acid Western", which is nothing if not accurate. In it, we see a struggle between several characters, and their memories. The story seems so simple on one level - it's a revenge story. It's almost, though not quite "I'm looking' for the man who shot my Pa" but mixed with a bit of the twisty, post-Modernist juju and a slow, desert drawl. The acting could be seen as either measured, or deliberate, and in either case, it's exactly the right choice for the material. It doesn't ping off the racket so much as it worms its way into the mind. The scene is so perfectly set that it can't help but feeling like a molasses wave traveling to catch every one in its sticky deathly goodness. The performance of Robert Scott Crane as Oliver Randall is particularly affective and effecting. His delivery, and especially his cadence, gives the film a path to walk along. There's also a silent, and breathtakingly haunting, performance from Brittany Slattery. Her look alone is enough to give a pastiche to the entire film, making us question our location in time and space, but she also gives off a sweetness without making too big a presence in the realm of screentime. I really think the secondary story for the feature version of Curio Shop could be all hers, but alas, I don't think that's in the cards. Yeah, it's a short and everyone knows that shorts are just entries for features, but the setting is so strong that it could support a feature.

Perhaps that's the best part of Curio Shop - the setting. There's a dream-like quality to the entire thing that feels as if it's taking place in either a past that never could have led to today, or a tomorrow uninfluenced by the events we understand. The world of weapons and weapons master, of powerful characters who are not easily trusting, nor swayed towards reason, and the visual sense that makes all of that seem reasonable, and even more impressive, actually like a reality. THAT is the greatest trick of Curio Shop - there is so much reality in the Surreality.

Perhaps the way the sound is presented makes for the most interesting moments. Listening to the score on its own reveals a strong influence from cinematic music ranging from the Spaghetti Western scores from Ennio Morricone, to some stuff that reminded me of nothing less than Philip Glass. It helps establish the characters and situations, but at the same time, it gives those viewers who aren't as in-touch with the Surrealist- bent of the material to experience it less as an Art FIlm (and I hope no one with the production is offended that I am calling it that!) and more as a Genre piece.

If I had any complaint, it's that the pacing is deliberate, and that leads to a slightly longer runtime than might have told the story. It's a heavy-hitter, and the extra moments build the characters nicely, but I can't imagine what I would have left out. At 18 minutes, it runs a touch long, and it feels a touch long, but none of it is wasted.

I have heard this referred to as a Steampunk film. I'm not sure, though there is certainly the aesthetic that they're playing with. Goggles, and brass, six-shooters. I'd almost say it was a Weird West Tale, if there wasn't a strange fantasy, or perhaps science fictional, element playing alongside I'd totally go in that direction. It's something different, something new, something that reeks of originality, but at the same time doesn't feel as if it is newborn.

In short, it's excellent.

For more information on Curio Shop, check out www.curioshopthemovie.com/

Facebook - www.facebook.com/CurioShopTheMovie

Twitter - https://twitter.com/CurioShopMovie

Let's talk about Surrealism. Not Dali, Man Ray, Kahlo. or Ernst, but more filmmakers like Buñel or Artaud or… well, Man Ray. Huh. I didn't see that one coming. Surrealist film, that branch of cinematic expression that attaches to the dream-like state of non-reality while still existing in a realm of possibilities, has many forms. Easily my favorite takes the form of black comedy, often combining elements of fantasy or science fiction with an avant grade sensibility. This is the milieu that the film Curio Shop inhabits, and one of the reasons you should seek it out.

The story of Curio Shop is described as a "Post-Apocalyptic Acid Western", which is nothing if not accurate. In it, we see a struggle between several characters, and their memories. The story seems so simple on one level - it's a revenge story. It's almost, though not quite "I'm looking' for the man who shot my Pa" but mixed with a bit of the twisty, post-Modernist juju and a slow, desert drawl. The acting could be seen as either measured, or deliberate, and in either case, it's exactly the right choice for the material. It doesn't ping off the racket so much as it worms its way into the mind. The scene is so perfectly set that it can't help but feeling like a molasses wave traveling to catch every one in its sticky deathly goodness. The performance of Robert Scott Crane as Oliver Randall is particularly affective and effecting. His delivery, and especially his cadence, gives the film a path to walk along. There's also a silent, and breathtakingly haunting, performance from Brittany Slattery. Her look alone is enough to give a pastiche to the entire film, making us question our location in time and space, but she also gives off a sweetness without making too big a presence in the realm of screentime. I really think the secondary story for the feature version of Curio Shop could be all hers, but alas, I don't think that's in the cards. Yeah, it's a short and everyone knows that shorts are just entries for features, but the setting is so strong that it could support a feature.

Perhaps that's the best part of Curio Shop - the setting. There's a dream-like quality to the entire thing that feels as if it's taking place in either a past that never could have led to today, or a tomorrow uninfluenced by the events we understand. The world of weapons and weapons master, of powerful characters who are not easily trusting, nor swayed towards reason, and the visual sense that makes all of that seem reasonable, and even more impressive, actually like a reality. THAT is the greatest trick of Curio Shop - there is so much reality in the Surreality.

Perhaps the way the sound is presented makes for the most interesting moments. Listening to the score on its own reveals a strong influence from cinematic music ranging from the Spaghetti Western scores from Ennio Morricone, to some stuff that reminded me of nothing less than Philip Glass. It helps establish the characters and situations, but at the same time, it gives those viewers who aren't as in-touch with the Surrealist- bent of the material to experience it less as an Art FIlm (and I hope no one with the production is offended that I am calling it that!) and more as a Genre piece.

If I had any complaint, it's that the pacing is deliberate, and that leads to a slightly longer runtime than might have told the story. It's a heavy-hitter, and the extra moments build the characters nicely, but I can't imagine what I would have left out. At 18 minutes, it runs a touch long, and it feels a touch long, but none of it is wasted.

I have heard this referred to as a Steampunk film. I'm not sure, though there is certainly the aesthetic that they're playing with. Goggles, and brass, six-shooters. I'd almost say it was a Weird West Tale, if there wasn't a strange fantasy, or perhaps science fictional, element playing alongside I'd totally go in that direction. It's something different, something new, something that reeks of originality, but at the same time doesn't feel as if it is newborn.

In short, it's excellent.

For more information on Curio Shop, check out www.curioshopthemovie.com/

Facebook - www.facebook.com/CurioShopTheMovie

Twitter - https://twitter.com/CurioShopMovie

Reviewed - The Fall by Kristof Hoornaert

Losing their way. a drive leads a couple into the deep forest. Once there, they make a terrible mistake, and battle over how to deal with it, and the consequences of those choices.

The Fall is a film that plays with what is unseen and unsaid; a film that relies on nuance and simple, largely static, camera shots, allowing two actors at the top of their craft to explore the intensity of the situation.

That’s the short form for this emotional masterwork. The real business here is the interaction between the actors, the cinematography, and their environment. Geert Van Rampelberg and Natali Broods are both electric playing off each other. Real chemistry, but that’s not even the best part. The connection between the performances and the shooting is incredible. They allow the long takes to drip off of them, to come into them, and that is the mark of an incredible actor.

The Belgian forest setting and the acting are what’s most amazing, though. The trees, the road, the inside of the Range Rover. These characters expand into all the available space. Two people in a Range Rover is nothing, but somehow, every inch is filled by the two of them. Their relationship is heavy, even before the action, and the silences between them all along is as telling as the actions taken after their fall into fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

Kristof Hoornaet’s direction is flawless, showing huge amounts of trust in his actors and his crew. They shot the whole thing in a single day, which takes huge amounts of guts, but can pay out in glory. The Fall is one of the most remarkable films of its type ever made.

The Fall is a film that plays with what is unseen and unsaid; a film that relies on nuance and simple, largely static, camera shots, allowing two actors at the top of their craft to explore the intensity of the situation.

That’s the short form for this emotional masterwork. The real business here is the interaction between the actors, the cinematography, and their environment. Geert Van Rampelberg and Natali Broods are both electric playing off each other. Real chemistry, but that’s not even the best part. The connection between the performances and the shooting is incredible. They allow the long takes to drip off of them, to come into them, and that is the mark of an incredible actor.

The Belgian forest setting and the acting are what’s most amazing, though. The trees, the road, the inside of the Range Rover. These characters expand into all the available space. Two people in a Range Rover is nothing, but somehow, every inch is filled by the two of them. Their relationship is heavy, even before the action, and the silences between them all along is as telling as the actions taken after their fall into fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

Kristof Hoornaet’s direction is flawless, showing huge amounts of trust in his actors and his crew. They shot the whole thing in a single day, which takes huge amounts of guts, but can pay out in glory. The Fall is one of the most remarkable films of its type ever made.

Interview - Sarah Smick of Friended to Death: Director, Actress, Writer

COMING TO A THEATRE NEAR YOU MAY 2nd!

Film Synopsis:

After having the worst day of his life, Facebook junkie Michael Harris begins to question whether his "Friends" are really his friends. Desperate for answers, he concocts a scheme to fake his death online just to see who shows up at his funeral. Ryan Hansen (Veronica Mars) stars in this hilarious examination of friendship in today’s hyper-‐connected world of social media.

1) OK, let's start with the obvious -‐ What's been your Social Media experience and footprint?

I’ve been on Facebook since virtually the beginning. The site rolled out to Columbia students during my freshman year, just a month after Zuckerberg first introduced it at Harvard. But like a lot of people, I’ve always been more of a casual user. I think social media is a useful surrogate for a rolodex and an incredibly efficient marketing tool, but, as you can tell from the film, I don’t think it’s a viable substitute for face-‐to-‐face connection.

I don't engage much on most other social platforms; however, I am unabashedly obsessed with Pinterest. For me, Pinterest is less of a social experience though, and more of a creative one. I use it as a digital inspiration board; a canvas to visualize and curate content around my passions. Whether or not my boards are public or other users interact with my pins doesn't tend to impact the value of my user experience a whole lot. In fact, I have quite a few private boards that I pin to more often than my public ones.

2) How much Text Speak ends up in your everyday conversation?

I’m not fluent, but it does come in handy at family gatherings where full fledge profanity seems inappropriate. Michael, the protagonist in Friended to Death, is a more extreme case than most, but people in general seem to be evermore proficient at text speak these days, both online and off. I think the film picks up on some of the blurred lines that have formed around our social vernacular and the way we communicate face-‐to-‐face as opposed to online.

3) What are the difficulties of both acting and directing at the same time? Do you even find yourself making decisions in one role that conflict with the other?

I cut my teeth on this a bit a few years ago when I directed and starred in a web series I created called “Old Souls.” It’s an exciting challenge to wear both hats at once. The prevailing concern, of course, is that you'll wear yourself too thin and compromise your work in both areas. But I couldn’t have asked for a better team around me to help pull everything together. We were all on the same page creatively, which allowed me to transition between my roles with more ease. My DP Jimmy Lu and I had spoken in depth during pre-‐production about how we wanted the film to look and feel. We did a ton of storyboarding as well. When we got to the shoot, Jimmy knew exactly what we were going for, so I felt free to focus on my acting and trust his ability to assess each take based on our pre-‐established vision. I, of course, wanted to see playback whenever time permitted, but honestly, Jimmy's got such a brilliant eye that it's easy (and wise) to trust his judgment regardless.

This dynamic of trust and preparation played out in all areas of the production with the entire crew. As far as my acting went, I relied a lot on the fact that I had co-‐written the script, meaning I had created my character from nothing and lived with her for nine or ten months before we shot. Having such intimate knowledge of a character that far in advance of shooting is a rare luxury in film and it made all of my jobs that much easier.

4) Walk us through your creation process, if you could? How did it start in your brains and what path did it take to get it on the screen?

We read an article about a guy who faked his own death (offline, not on) and held a funeral service that only his mother attended. The man then proceeded to write 44 hand-‐written letters to his friends, chastising them for not showing up. We asked ourselves, “what kind of a guy would do something that extreme?” What you see in Michael’s character is our own exploration of that very question. Being well versed in comedy, we wanted to tackle the topic of fake death from that quite unexpected angle. Comedy also seemed to offer opportunities for irony and satiric social critique in the film, which drama did not. So we pushed the comedy hard, using the tongue-in-‐cheek “bro-‐mance” and over-‐the-‐top, man-‐child type characters to comment on the larger issue of social media and its influence on our real-‐world relationships.

As we approached production, I began to hone my vision for the look of the film. I wanted it to look cinematic to underscore Michael's narcissistic grandiosity. That's why I opted for the more epic-‐feeling 2.39 aspect ratio and why we prioritized production value. Now that I've seen the film on the big screen a few times, I'm glad I made those choices. I will say that I learned a lot about how decisions you make early on in the filmmaking process come to bear on the finished product. That's not to say that I would change things about the film, but rather that I'm more aware now of the tools I have at my disposal.

5) You've got an amazingly talented cast. No question here, just wanted to say that.

Thank you, and I agree! I can’t say enough about the professionalism, openness and raw talent each of our cast members brought to the table every day. Even as we wrote the script, we knew we needed actors who could nail the film's quirky characters and distinct tone. Not only that, they needed to have chemistry with each other. Fortunately, we had an incredibly talented and resourceful casting director, Nicole Arbusto, who helped us pull that off.

6) Since you've lived the film for so long, how does it feel now that it's premiered? Can you watch the film and not get caught up in the feelings from creating it?

To be honest, I still can’t watch the film without laughing out loud (LOL). There’s always something new that I pick up on with each successive viewing. I’m obviously fond of the script, but I think the film’s replay value is also a testament to the impeccable timing and improvisational skills of our cast.

7) What do you want audiences to walk out of the theatre thinking/feeling?

I want the audience to feel genuinely entertained, and since the film does have heart, I hope people can connect emotionally to it as well. In addition, and just as importantly, I'd like viewers to read between the lines and detect the social media commentary that's woven into the film's subtext. The characters are so overtly flawed and over-‐the-‐top, and their humor is so off-‐putting at times, it's hard not to detect some level of irony on the part of the filmmaker. My hope is that people will sense that irony and what it's saying about our culture, rather than take the film at face value as an endorsement of offensive jokes or a glorification of the "man-‐child" phenomenon. Social media has shaped our culture in profound and dangerous ways. The characters in this film, their pathos and their damaged relationships, are a reflection of that reality. I hope audiences think about that and how it might be playing out in their own lives.

8) What can we expect from y'all next?

We've got a number of other scripts and treatments in development that we're moving on next. Most have a comedic bent to them as that's our wheelhouse, but we are always open to other genres should the right idea come along. We're looking at an interesting project in the documentary world as well, so stay tuned!

See Friended to Death in theatres across the country on May 2nd, 2014!

https://www.facebook.com/events/673646496016728/ for more details!

Victoriana - Directed by Jadrien Steele

Victoriana doesn’t bother even trying to be that story you keep hearing - young people facing a difficult problem, sticking to their ideals and triumphing. Instead, what Victoriana does is work magic by giving us one-part tragedy for equal parts victory. Here, where lesser films would insist on the the characters growing and learning, director and writer make a much more realistic, and cynical, choice. Yes, they change, almost universally for the worse, and it’s a good thing. A very good thing for those of us viewing it through the pinhole. I get tired of the feel-good ending, and here, it’s not at all a feel-good; it’s far more of a “Yeah, that’s how it would happen.”

Sophie Becker has a trust fund. She convinces her writer husband Tim that they should buy and renovate a brownstone in Brooklyn. Now, they start out with high ideals- they’re not going to throw out the current residents of the brownstone because they don’t want to be a part of the gentrification that has often priced-out so many long-time residents. They set about remodeling the house, turning it into five apartments, only to see troubles pop up in every corner. There’s an elderly tenant, Louise, who’s been there since the 50s, who also happens to be a total jerk. The renovation costs keep going up and up, and the money’s running out. Tim, an author, is let go by his agent, but he decides to lie to Sophie and say that everything’s great. The money isn’t flowing, Tim’s creative juices are equally dried up, and the strain it’s putting on their marriage is considerable.

As the film moves forward, both Tim and Sophie make massive mistakes in dealing with their situations. It seems as if every time they make a choice, it’s consequences lead to more pain between them, and even further complications outside. They start to let themselves change. The couple that would not assist in the gentrification of their little part of Brooklyn become cold, heartless. Tim faces reality and takes a job with a cutthroat real estate company. Sophie doggedly pursues the renovations, and an affair with the renovator. There’s also the problem of the police snooping about due to the disappearance of Louise. Every choice they make is almost certainly wrong, morally speaking, but every one is the one I’d probably in the same circumstances.

All along, one can tell that this story will not end well; the outcome is obvious from the time the first choice is made. The problem is they are flawed, they’re humans, and they have started down a path. They make moves that can only end in one thing, and they change, not growing, but learning how to deaden parts of themselves to move further down the path. They abandon those morals and become people, not crusaders. That’s a difficult matter when it comes to acting. You can lean into it, play it for comedy like in the film Life Stinks, but here, Jadrien Steele and Marguerite French play these situations perfectly. French’s Sophie, in particular, is amazing. She plays remorse in equal portions with resolve, all while managing to get across the idea of a woman caught in a bear trap. Tim becomes completely unlikeable, not that Sophie is all that likable as time goes on, but he really does turn into a dirtbag.

And in the same situation, so would I.

Perhaps the best way to look at Victoriana is through the lens of compromise. Almost from the first scene, the characters making bigger and bigger compromises, to the point that at the end, there’s nothing left of their original characters: but they’ve won. The material goal of the characters from the beginning is achieved, but they are no longer themselves; they are the compromised versions of themselves, which are deplorable, but completely understandable. The Grand Compromise that comes as the finale of the film must be so disheartening to any viewer who wants a happy ending. What we are given is merely another compromise, and that is actually what happens in life. There are no bows, there are no real endings. There is compromise after compromise until the moment when you have no remaining compromises to make. THAT is the ending of all of us, and that is the ending of Victoriana.

Sophie Becker has a trust fund. She convinces her writer husband Tim that they should buy and renovate a brownstone in Brooklyn. Now, they start out with high ideals- they’re not going to throw out the current residents of the brownstone because they don’t want to be a part of the gentrification that has often priced-out so many long-time residents. They set about remodeling the house, turning it into five apartments, only to see troubles pop up in every corner. There’s an elderly tenant, Louise, who’s been there since the 50s, who also happens to be a total jerk. The renovation costs keep going up and up, and the money’s running out. Tim, an author, is let go by his agent, but he decides to lie to Sophie and say that everything’s great. The money isn’t flowing, Tim’s creative juices are equally dried up, and the strain it’s putting on their marriage is considerable.

As the film moves forward, both Tim and Sophie make massive mistakes in dealing with their situations. It seems as if every time they make a choice, it’s consequences lead to more pain between them, and even further complications outside. They start to let themselves change. The couple that would not assist in the gentrification of their little part of Brooklyn become cold, heartless. Tim faces reality and takes a job with a cutthroat real estate company. Sophie doggedly pursues the renovations, and an affair with the renovator. There’s also the problem of the police snooping about due to the disappearance of Louise. Every choice they make is almost certainly wrong, morally speaking, but every one is the one I’d probably in the same circumstances.

All along, one can tell that this story will not end well; the outcome is obvious from the time the first choice is made. The problem is they are flawed, they’re humans, and they have started down a path. They make moves that can only end in one thing, and they change, not growing, but learning how to deaden parts of themselves to move further down the path. They abandon those morals and become people, not crusaders. That’s a difficult matter when it comes to acting. You can lean into it, play it for comedy like in the film Life Stinks, but here, Jadrien Steele and Marguerite French play these situations perfectly. French’s Sophie, in particular, is amazing. She plays remorse in equal portions with resolve, all while managing to get across the idea of a woman caught in a bear trap. Tim becomes completely unlikeable, not that Sophie is all that likable as time goes on, but he really does turn into a dirtbag.

And in the same situation, so would I.

Perhaps the best way to look at Victoriana is through the lens of compromise. Almost from the first scene, the characters making bigger and bigger compromises, to the point that at the end, there’s nothing left of their original characters: but they’ve won. The material goal of the characters from the beginning is achieved, but they are no longer themselves; they are the compromised versions of themselves, which are deplorable, but completely understandable. The Grand Compromise that comes as the finale of the film must be so disheartening to any viewer who wants a happy ending. What we are given is merely another compromise, and that is actually what happens in life. There are no bows, there are no real endings. There is compromise after compromise until the moment when you have no remaining compromises to make. THAT is the ending of all of us, and that is the ending of Victoriana.

A for Alex by Alex Orr

I was utterly thrown when I watched A for Alex, the latest from Atlanta's Fake Wood Wallpaper. These are the same folks who put out Blood Car, one of the best horror films I've ever seen a Cinequest, and also Congratulations, the absolutely genius surrealist cop work from last year's festival. So, I had an idea of what to expect from A for Alex.

Only, I was not prepared. Not in the slightest.

Alex Orr, our director, is making a movie with his pregnant wife, Katie. The movie's about Alex Orr, our director, who is making a movie with his pregnant wife, Katie. That Alex is also an inventor, who has set out to replace the bees that have been dying off with much larger robotic bees. He's also full of existential angst about the impending arrival of his child, so much so that he spends a great deal of time crying. As time goes by, his film takes some turns for the worst, as his actors start to question his vision and rebel, and his bees, well, they're not great either.

This film is just so damned weird. It's a wonderful study in what soon-to-be-father's feel when they are thrown into the situation of having their first kid. Katie Orr, who is amazing in this film, is so rock solid, even when going through the ups and downs, and it seems that Alex is replacing the expectations of what her anxieties should be. At the same time, Alex does rise to the occasion sometimes, which only makes his failings feel more painful. He's not ready for this at all, and he's put so much on it, possibly because of his relationship with his father. We don't see any actual interactions with Alex's father, but an actor playing his father blows-up at him before Alex actually gets to say what the issues with his dad were. It's a nice touch, and the kind of thing that set me off my anticipation seat.

And then there's Alex's mother, who is obsessively posting videos of Alex from his youth. Sadly, she's not discriminate enough about what she posts and gets pinched for posting child pornography of her son getting blown as a fourteen year old. This thread is so weird, but it's also a bit telling of why Alex has this vision of a movie of his life, as it is really happening, and his desire to push the direction of it.

Of course, Katie Orr was actually pregnant, and we even get to see the young 'un as soon as he's born. The way the film is constructed is so smart. It plays with your expectations, especially for those who are so familiar with the filmmaker film you find in works like 9. It's all the artist's insecurities, showing that cinematic competence is so often masking emotional incompetence. It's a great film for that, and when it swings from one reality to another, it's jarring in a good way.

I can't recommend A for Alex enough, though you have to come to it with a will for the weird. It rewards those who come to it with perfect faith that they're gonna be fucked with!

Only, I was not prepared. Not in the slightest.

Alex Orr, our director, is making a movie with his pregnant wife, Katie. The movie's about Alex Orr, our director, who is making a movie with his pregnant wife, Katie. That Alex is also an inventor, who has set out to replace the bees that have been dying off with much larger robotic bees. He's also full of existential angst about the impending arrival of his child, so much so that he spends a great deal of time crying. As time goes by, his film takes some turns for the worst, as his actors start to question his vision and rebel, and his bees, well, they're not great either.

This film is just so damned weird. It's a wonderful study in what soon-to-be-father's feel when they are thrown into the situation of having their first kid. Katie Orr, who is amazing in this film, is so rock solid, even when going through the ups and downs, and it seems that Alex is replacing the expectations of what her anxieties should be. At the same time, Alex does rise to the occasion sometimes, which only makes his failings feel more painful. He's not ready for this at all, and he's put so much on it, possibly because of his relationship with his father. We don't see any actual interactions with Alex's father, but an actor playing his father blows-up at him before Alex actually gets to say what the issues with his dad were. It's a nice touch, and the kind of thing that set me off my anticipation seat.

And then there's Alex's mother, who is obsessively posting videos of Alex from his youth. Sadly, she's not discriminate enough about what she posts and gets pinched for posting child pornography of her son getting blown as a fourteen year old. This thread is so weird, but it's also a bit telling of why Alex has this vision of a movie of his life, as it is really happening, and his desire to push the direction of it.

Of course, Katie Orr was actually pregnant, and we even get to see the young 'un as soon as he's born. The way the film is constructed is so smart. It plays with your expectations, especially for those who are so familiar with the filmmaker film you find in works like 9. It's all the artist's insecurities, showing that cinematic competence is so often masking emotional incompetence. It's a great film for that, and when it swings from one reality to another, it's jarring in a good way.

I can't recommend A for Alex enough, though you have to come to it with a will for the weird. It rewards those who come to it with perfect faith that they're gonna be fucked with!

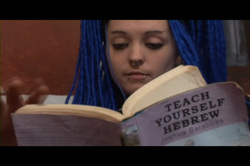

Learning Hebrew by Louis Joon

I watched a film called Jubilee once. It's a Derek Jarman film, and it rather defined the strange form of Punk Rock that was English in the 1970s. It's a remarkable document of the times, and a very very strange one. it took me two goes to make it through once, and then another three or four viewings to really understand some of it. Adam Ant's in it, which is nice. Ultimately, the power of the film is in the rough vision that Jarman formed using actors and situations that made little sense until put into the context of 1977 Punk Rock England. In a way, Jubilee is a Formalist reviewer's worst nightmare, because to get anything out of it, you have to go all the way out of the film. Still, it makes an impact.

I came across a film called Learning Hebrew, which is one of those films of today that seem to live in the spirit of Jubilee.

The film visually owes a lot to the shooting of films like Jubilee and Oliver Stone's l990s legendary triple visionary masterworks - The Doors, JFK, and Natural Born Killers. Fast editing, varying levels of saturation, black-and-white mixing with color, a generally disjointed sense of place and time's passage. It's a post-modernist vision, without question. It's a world that exists without time, but not in the way that Tim Burton's Batman approaches the same idea. It's a modern, right now time, but it's full of imagery that could exist in the past, present, or future of some discarded reality. Don't worry, you'll never confuse this world for one that has ever come to be.

The costumes and make-up, more than anything, give off an incredible impression of displacement. The clothing is alternately gorgeous and disarming. At times, there are just a bunch of Goths walking through a park, eating Vegan ice cream, and making for a damn fine view.

Ultimately, the script owes a lot to some of the films of the 90s that made me smile. Richard Linkletter's classic Slacker is probably the closest in terms of tone, though it is certainly more directed towards an idea. Laser-like its needle points at the idea of religion being bad, of the Government beign able to shut-down all discussion of anti-religious matters. At time, the film holds up Dawkins and Hitchins as near deities, but also exploring an idea of Humanism that seems less, I don't know, militant. At the same time, there's mocking of that non-militant strain called Agnosticism, at least a little. I love the concept of Evolutionists going out calling 'round trying to get folks to accept Charles Darwin as their Lord and Personal Savior. OK, that's not really the case, but they do go door-to-door trying to get people to let them in to talk about Natural Selection. It's a good bit! I've always wanted the world to be more Vonnegut than Dawkins. Yes, there is a militant strip to a lot of it, especially in the ending, but at the same time, it feels like we're being gently bashed over the head with the concept. I don't mean that as a knock- this is a story that lives in an amped world where all humans face amped-up actions, both in the present and the past. There's is timeslip, or maybe it's more time-shift, and the tone is consistent between it all.

The acting is OK, at times a bit rough, too direct. It's more like an actor saying lines than a person experiencing something and reacting to it. Does it distract from the ideas? Not really. They've managed to create a deeply grooved trail, and there's nothing that can distract from it. Still, it's not ideal. There are moments, such as Juliana Reed as The Dom in what I'd say was the most stunning scene in the whole film. It's not shocking subject matter, we've seen this sort of thing for more than three decades now, but there's a sort of interplay between The Dom and Dave Disaster as StudD, that is very impressive.

Visually, this is a wonder, and the music is spectacular. A picture is painted in the audio track, which can not be over-looked. The tone is set through the music. In a way, music is the sauce; visuals are the meat, and the actors, and ultimately the script, are the platter. They are the base for everything, but you don't really count them as the important part.

At a touch over an hour, Learning Hebrew is as fascinating as Jubilee, as frenetic as any Guy Ritchie film. It's a car crash of a sort, an art film that isn't trying to be an art film. Maybe it's trying to be one of those early 90s Goth zines, glossy cutouts of girls in latex and guys flicking cigarettes at cameras, all photocopied and distributed at coffee shops. That is the feeling I get, a familiar and lovely feeling, and one I enjoy.

I came across a film called Learning Hebrew, which is one of those films of today that seem to live in the spirit of Jubilee.

The film visually owes a lot to the shooting of films like Jubilee and Oliver Stone's l990s legendary triple visionary masterworks - The Doors, JFK, and Natural Born Killers. Fast editing, varying levels of saturation, black-and-white mixing with color, a generally disjointed sense of place and time's passage. It's a post-modernist vision, without question. It's a world that exists without time, but not in the way that Tim Burton's Batman approaches the same idea. It's a modern, right now time, but it's full of imagery that could exist in the past, present, or future of some discarded reality. Don't worry, you'll never confuse this world for one that has ever come to be.

The costumes and make-up, more than anything, give off an incredible impression of displacement. The clothing is alternately gorgeous and disarming. At times, there are just a bunch of Goths walking through a park, eating Vegan ice cream, and making for a damn fine view.

Ultimately, the script owes a lot to some of the films of the 90s that made me smile. Richard Linkletter's classic Slacker is probably the closest in terms of tone, though it is certainly more directed towards an idea. Laser-like its needle points at the idea of religion being bad, of the Government beign able to shut-down all discussion of anti-religious matters. At time, the film holds up Dawkins and Hitchins as near deities, but also exploring an idea of Humanism that seems less, I don't know, militant. At the same time, there's mocking of that non-militant strain called Agnosticism, at least a little. I love the concept of Evolutionists going out calling 'round trying to get folks to accept Charles Darwin as their Lord and Personal Savior. OK, that's not really the case, but they do go door-to-door trying to get people to let them in to talk about Natural Selection. It's a good bit! I've always wanted the world to be more Vonnegut than Dawkins. Yes, there is a militant strip to a lot of it, especially in the ending, but at the same time, it feels like we're being gently bashed over the head with the concept. I don't mean that as a knock- this is a story that lives in an amped world where all humans face amped-up actions, both in the present and the past. There's is timeslip, or maybe it's more time-shift, and the tone is consistent between it all.

The acting is OK, at times a bit rough, too direct. It's more like an actor saying lines than a person experiencing something and reacting to it. Does it distract from the ideas? Not really. They've managed to create a deeply grooved trail, and there's nothing that can distract from it. Still, it's not ideal. There are moments, such as Juliana Reed as The Dom in what I'd say was the most stunning scene in the whole film. It's not shocking subject matter, we've seen this sort of thing for more than three decades now, but there's a sort of interplay between The Dom and Dave Disaster as StudD, that is very impressive.

Visually, this is a wonder, and the music is spectacular. A picture is painted in the audio track, which can not be over-looked. The tone is set through the music. In a way, music is the sauce; visuals are the meat, and the actors, and ultimately the script, are the platter. They are the base for everything, but you don't really count them as the important part.

At a touch over an hour, Learning Hebrew is as fascinating as Jubilee, as frenetic as any Guy Ritchie film. It's a car crash of a sort, an art film that isn't trying to be an art film. Maybe it's trying to be one of those early 90s Goth zines, glossy cutouts of girls in latex and guys flicking cigarettes at cameras, all photocopied and distributed at coffee shops. That is the feeling I get, a familiar and lovely feeling, and one I enjoy.

Gleb Osatinski's The House at the Edge of the Galaxy - Reviewed by Chris Garcia

A lonely child is the saddest of all possible conditions. We all remember our childhoods, right? We remember the wonder or the terror, the joy or the pain. We remember the feeling of it, and though the days and years that have passed, we have had those feelings multiplied, amplified, distorted; ether positively or negatively. I can remember the feeling I got the first time I rode a roller coaster: that feeling in the bottom of my stomach. The world was strange then, right? There were new things everywhere you looked, and some things were magic.

A short film that touches on that feeling is Gleb Osatinski's The House at the Edge of the Galaxy.

The story, when broken down for dinner party conversation, is delightfully simple. A cosmonaut lands at a house where a young child lives alone. The kid says he has no name. The cosmonaut has been out in space for a long time. The two of them converse and the cosmonaut gives our child a star seed to plant in his garden.

To say much more would put down that child in all of us through over-abundance of information.

This is a story of absolute beauty. The ramshackle house is set in the middle of a forest and every shot that shows it is nearly breathtaking. It brings about that feeling you get from things like Twin Peaks: as if between the trees are captured spirits that inhabit every frame of the picture. The cinematography of The House on the Edge of the Galaxy is beautiful, and more than a bit haunting. The way the interiors of the house itself are shot lives you wondering what's the reality of this kid's world, and why are there so many pictures, so many reminders of a world that is obviously long gone, far away, on the other side of those trees.

The score is also of note, because not only does it seem to haunt, but it feels as if the gentle piano is coming from within the house, out the door falling off its hinges, into the forest. I was reminded of some of my favorite scores, particularly, and possibly for no good reason, Phillip Glass' score for The Hours. It was beautiful, the kind of score you could listen to outside of the film itself. It helps establish this scene, this house in the middle of the woods, as another place.

The Cosmonaut is odd. He arrives with no fanfare, no great crash of his ship into the woods, no powerful moment of entry into the atmosphere. At least none that we see. We are led to believe that he has traveled from far away, that he has put millions of miles on that orange spacesuit.

But has he?

Is he really a cosmonaut? That might be the central question of the film. If he is, why has he landed, what does he need? If he is not, why does he claim to be? The multiple viewings I made of this short led me to several different readings. At times, he is a cosmonaut, his ship just on the other side of the rise, near the birch trees. Other viewings, he's a fraud, come for some purpose we never get to understand. Some viewings, he is not a cosmonaut, but something greater; greater than man and probably closer to gods or monsters. And in others, he's just an imaginary friend the nameless child has invented to keep himself company.

But always, there are those pictures.

The walls of the house, even with all the peeling wallpaper and chipping paint, are covered with framed photos. Why? If there are so many others out there, even if in some distant past, why is the kid left there, alone? Who are they? Has the kid simply come across this place and turned it into his home, or has he always been there, always alone; alone with the images of a past he can have no connection to. Is that the message? The cosmonaut is no less distant a figure than the people in those pictures. The kid is so distant from the world, stuck in that house, that he may well have been in space for longer than that cosmonaut. He is so distant.

And though I'm not sure if it was an intentional choice or not, a couple of the exchanges between the cosmonaut and the kid pulled me slightly out of the film. This is the first role for Grayson Sides and there is a lot to learn from it. While he played well with the camera, his presence and charisma felt throughout, some of his lines felt distant and alienated. While it was Sides' job to play lost and found in time and space, perhaps these lines had to feel more attached to the present. Still, when you are acting against a cosmonaut, to hold your own is an admirable task. I'm excited to see what he follows this with, as there is obviously talent in the kid.

Still, this is a short that is at once fantasy and science fiction. The markers of both exist, in some ways reminding me of LOST. What is the house and who is the kid? What is as it seems? It is a fool who believes everything he is shown, and a bigger fool who believes nothing he is shown. This film seems to be a sort of test of that idea. How much can we believe, and what marks the truth anyhow. The ending of the short leaves the two biggest questions I had unanswered, and that only made me want to discover more.

You can find out more at http://houseattheedgeofgalaxy.com

A short film that touches on that feeling is Gleb Osatinski's The House at the Edge of the Galaxy.

The story, when broken down for dinner party conversation, is delightfully simple. A cosmonaut lands at a house where a young child lives alone. The kid says he has no name. The cosmonaut has been out in space for a long time. The two of them converse and the cosmonaut gives our child a star seed to plant in his garden.

To say much more would put down that child in all of us through over-abundance of information.

This is a story of absolute beauty. The ramshackle house is set in the middle of a forest and every shot that shows it is nearly breathtaking. It brings about that feeling you get from things like Twin Peaks: as if between the trees are captured spirits that inhabit every frame of the picture. The cinematography of The House on the Edge of the Galaxy is beautiful, and more than a bit haunting. The way the interiors of the house itself are shot lives you wondering what's the reality of this kid's world, and why are there so many pictures, so many reminders of a world that is obviously long gone, far away, on the other side of those trees.

The score is also of note, because not only does it seem to haunt, but it feels as if the gentle piano is coming from within the house, out the door falling off its hinges, into the forest. I was reminded of some of my favorite scores, particularly, and possibly for no good reason, Phillip Glass' score for The Hours. It was beautiful, the kind of score you could listen to outside of the film itself. It helps establish this scene, this house in the middle of the woods, as another place.

The Cosmonaut is odd. He arrives with no fanfare, no great crash of his ship into the woods, no powerful moment of entry into the atmosphere. At least none that we see. We are led to believe that he has traveled from far away, that he has put millions of miles on that orange spacesuit.

But has he?

Is he really a cosmonaut? That might be the central question of the film. If he is, why has he landed, what does he need? If he is not, why does he claim to be? The multiple viewings I made of this short led me to several different readings. At times, he is a cosmonaut, his ship just on the other side of the rise, near the birch trees. Other viewings, he's a fraud, come for some purpose we never get to understand. Some viewings, he is not a cosmonaut, but something greater; greater than man and probably closer to gods or monsters. And in others, he's just an imaginary friend the nameless child has invented to keep himself company.

But always, there are those pictures.

The walls of the house, even with all the peeling wallpaper and chipping paint, are covered with framed photos. Why? If there are so many others out there, even if in some distant past, why is the kid left there, alone? Who are they? Has the kid simply come across this place and turned it into his home, or has he always been there, always alone; alone with the images of a past he can have no connection to. Is that the message? The cosmonaut is no less distant a figure than the people in those pictures. The kid is so distant from the world, stuck in that house, that he may well have been in space for longer than that cosmonaut. He is so distant.

And though I'm not sure if it was an intentional choice or not, a couple of the exchanges between the cosmonaut and the kid pulled me slightly out of the film. This is the first role for Grayson Sides and there is a lot to learn from it. While he played well with the camera, his presence and charisma felt throughout, some of his lines felt distant and alienated. While it was Sides' job to play lost and found in time and space, perhaps these lines had to feel more attached to the present. Still, when you are acting against a cosmonaut, to hold your own is an admirable task. I'm excited to see what he follows this with, as there is obviously talent in the kid.

Still, this is a short that is at once fantasy and science fiction. The markers of both exist, in some ways reminding me of LOST. What is the house and who is the kid? What is as it seems? It is a fool who believes everything he is shown, and a bigger fool who believes nothing he is shown. This film seems to be a sort of test of that idea. How much can we believe, and what marks the truth anyhow. The ending of the short leaves the two biggest questions I had unanswered, and that only made me want to discover more.

You can find out more at http://houseattheedgeofgalaxy.com

A Staged Reading of A Computer Simulation of God by David Voda - Reviewed by Chris Garcia

Often, you are a crossroads. You stand somewhere and someone comes to you, many someones, and they are connected by something deeper than you'd expect, and no one had any idea that it was there, and when it is discovered, it all makes sense.

This happens to me frequently. I find myself encountering people and events which are tied to many areas of my life. Such happened with the staged reading of A Computer Simulation of God held on June 23rd at the Computer History Museum.

The staged reading was the premiere of David Voda's script. Voda is a screenwriter and producer whose film The Secretary won acclaim at festivals. I'd never heard of his work before reading about the reading. What can I say, I'm not as tied in as much as I'd like. As a younger gentleman in Pittsburgh, he had worked with computers. This was an earlier time, when mainframes like the IBM 360 and minicomputers like Digital Equipment Corporation's PDP-series of computers ruled the pre-PC world. This was the world in which A Computer Simulation of God was set. A world which I have been witnessing from afar for almost 15 years.

As a curator at the Computer History Museum, I've been working with the relics of the 1960s computing scene for almost fifteen years. I've encountered not only the machines, but the ephemera, the documentation, the software, and especially the people who defined this era. While my own expertise in the area of computers is the 1970s-early 90s, it is this era of skinny ties and pressed white shirts feeding punched cards and paper tape into hulking machines that I've worked documenting for most of my career. It is this setting, or more precisely, in a Catholic school in Pittsburgh, that young Ray Novak (read by Bo Krucik) lives out his days. It seems he has been bound for the seminary since birth, but he is a curious type; a young man who is obsessed with visions of technology, both real and imagined. He is obsessed with a novel, a science fiction novel in fact, that details a Universe where a computer is the most powerful being of all. He is lead by these visions of computation to the lab of Dr. Weisman (Johnny Gilligan), who runs the computer lab at the local University. He is also a part of various secrets, including the fact that he writes science fiction for companies such as Ace.

If there is an area I have studied more than computers, it is science fiction. I've been a fan since birth, and have been luckily enough to meet and befriend a number of the writers of the 1960s through to today. I know many Professors of various types who have lived a pair of lives: one as a professional and one as a writer of SciFi. Norbert Wiener, the founder of the Cybernetics, wrote under the name W. Norbert, and John Pierce, the man who named the Transistor and arguably the first name in the history of Computer Music, wrote as J.J. Coupling. Of course, for ever Wiener and Coupling there are folks like Asimov or Rudy Rucker who are out and proud with their SF writing while still making impressions on academia.

The story begins with a car accident in which Ray's father is injured and ends up in a vegetative state. While Ray is dealing with this, he is also discovering computers. It is the collision between his fascination with electronic computing and his processing of his grief for his plateauing father. It is out of this combination that Ray designs a program that is A Computer Simulation of God. He enters the catechism into the computer and it begins to answer questions as if it were God.

Naturally, this does not go over well with the Powers that be of the Catholic school.

Few realise how often computers have been used by religious institutions. In ancient times, analog contraptions were used to determine the dates for moveable feasts such as Easter. The UNIVAC computer was used to create the Complete Concordance of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. By the 1960s, there were many Catholic universities beginning to teach computing, which makes sense. The Church is often seen as being against technological advance, but at times the Catholic Church has done much to advance science, and computers are no exception.

This is not the only story told in script. In fact, the way the reading was broken up by an intermission devided the story into two genres: family drama to begin, science fiction to finish. In the early portion, Susan Monson, who I've seen in many productions over the years, brought a wonderful sense of determination, resolve, and flat-out exasperation, to playing Helen Novak. Her take on the character provided much of the heart of the first half of the reading. Ray couldn't actually provide that sense as he was in the midst of discovering the world of technology. His sister Dot, read by Ashley Rae, is dealign with her own life and love and the difficulties of her father's condition all at the same time. Her read on Dot is a bit spread, and her interactions with Tommy (Ian Paterson) are at times charmingly sweet and bitterly pained. She was well-cast, no doubt.

In the second half, we discover that this is not only a familial drama, but a science fiction story: a tale of the effect of a change in the level of technology compared to what is actually available. This is the kind of science fiction that is not outer space aliens and blasters, but a science fiction of ideas, application. The program Ray creates is basically a Chatbot, closely related to ELIZA, a computer simulation of a psychotherapist's technique designed in the 1960s by Dr. Joseph Weizenbaum. The application to the catechism is novel, and a staple of SciFi themes. Take a technology that exists, apply it to an area where it had never existsed before and BAM! An excellent example of this is Arthur C. Clarke's Nine Billion Names for God, in which a computer is placed to a Buddhist temple's long-standing task of recording all the possible names for God.

And A Computer Simulation of God compares favorably with Clarke's work. It is a strong call for reason and faith to interact, and how each can provide solace. That is not exactly the message of the piece, but it hit me in that way. I've studied religion, have a degree in Comparative Religion, and I can see that we look towards mysteries for our comfort. Computers are a form of mystery, or at least they were in the 1960s, and I can understand how the unquestionable logic of the machine when seen in contrast of what the rest of the world presents, could provide the ultimate form of solace for one walking through the valleys of pain.

The script is a touch stagey, though a staged reading lends itself to the delivery of material in a stagey way. The actors read with wonderful emotion and came through with the messages of the script underlined very well indeed. The material presented, which I felt an easy connection and appreciation for, is well-researched and the accuracy of the era is remarkable, but the emotional content is just as accurate, and that is every bit as important.

Perhaps there is a force that draws like minds towards material that goes deep into their soul unconsciously. There is no other person I can think of who had as many points of contact, both concrete and conceptual, with the material that is found in A Computer Simulation of God. On the other hand, even without that connection, it is a remarkable piece of writing. It has won acclaim in screenwriting competitions, understandably, and is currently being produced for the screen by Smokey Pictures. When it finally makes its way to the screen, see it. It will raise questions and entertain, and ultimately that is the outcome of the best films.

This happens to me frequently. I find myself encountering people and events which are tied to many areas of my life. Such happened with the staged reading of A Computer Simulation of God held on June 23rd at the Computer History Museum.

The staged reading was the premiere of David Voda's script. Voda is a screenwriter and producer whose film The Secretary won acclaim at festivals. I'd never heard of his work before reading about the reading. What can I say, I'm not as tied in as much as I'd like. As a younger gentleman in Pittsburgh, he had worked with computers. This was an earlier time, when mainframes like the IBM 360 and minicomputers like Digital Equipment Corporation's PDP-series of computers ruled the pre-PC world. This was the world in which A Computer Simulation of God was set. A world which I have been witnessing from afar for almost 15 years.

As a curator at the Computer History Museum, I've been working with the relics of the 1960s computing scene for almost fifteen years. I've encountered not only the machines, but the ephemera, the documentation, the software, and especially the people who defined this era. While my own expertise in the area of computers is the 1970s-early 90s, it is this era of skinny ties and pressed white shirts feeding punched cards and paper tape into hulking machines that I've worked documenting for most of my career. It is this setting, or more precisely, in a Catholic school in Pittsburgh, that young Ray Novak (read by Bo Krucik) lives out his days. It seems he has been bound for the seminary since birth, but he is a curious type; a young man who is obsessed with visions of technology, both real and imagined. He is obsessed with a novel, a science fiction novel in fact, that details a Universe where a computer is the most powerful being of all. He is lead by these visions of computation to the lab of Dr. Weisman (Johnny Gilligan), who runs the computer lab at the local University. He is also a part of various secrets, including the fact that he writes science fiction for companies such as Ace.

If there is an area I have studied more than computers, it is science fiction. I've been a fan since birth, and have been luckily enough to meet and befriend a number of the writers of the 1960s through to today. I know many Professors of various types who have lived a pair of lives: one as a professional and one as a writer of SciFi. Norbert Wiener, the founder of the Cybernetics, wrote under the name W. Norbert, and John Pierce, the man who named the Transistor and arguably the first name in the history of Computer Music, wrote as J.J. Coupling. Of course, for ever Wiener and Coupling there are folks like Asimov or Rudy Rucker who are out and proud with their SF writing while still making impressions on academia.

The story begins with a car accident in which Ray's father is injured and ends up in a vegetative state. While Ray is dealing with this, he is also discovering computers. It is the collision between his fascination with electronic computing and his processing of his grief for his plateauing father. It is out of this combination that Ray designs a program that is A Computer Simulation of God. He enters the catechism into the computer and it begins to answer questions as if it were God.

Naturally, this does not go over well with the Powers that be of the Catholic school.

Few realise how often computers have been used by religious institutions. In ancient times, analog contraptions were used to determine the dates for moveable feasts such as Easter. The UNIVAC computer was used to create the Complete Concordance of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible. By the 1960s, there were many Catholic universities beginning to teach computing, which makes sense. The Church is often seen as being against technological advance, but at times the Catholic Church has done much to advance science, and computers are no exception.

This is not the only story told in script. In fact, the way the reading was broken up by an intermission devided the story into two genres: family drama to begin, science fiction to finish. In the early portion, Susan Monson, who I've seen in many productions over the years, brought a wonderful sense of determination, resolve, and flat-out exasperation, to playing Helen Novak. Her take on the character provided much of the heart of the first half of the reading. Ray couldn't actually provide that sense as he was in the midst of discovering the world of technology. His sister Dot, read by Ashley Rae, is dealign with her own life and love and the difficulties of her father's condition all at the same time. Her read on Dot is a bit spread, and her interactions with Tommy (Ian Paterson) are at times charmingly sweet and bitterly pained. She was well-cast, no doubt.

In the second half, we discover that this is not only a familial drama, but a science fiction story: a tale of the effect of a change in the level of technology compared to what is actually available. This is the kind of science fiction that is not outer space aliens and blasters, but a science fiction of ideas, application. The program Ray creates is basically a Chatbot, closely related to ELIZA, a computer simulation of a psychotherapist's technique designed in the 1960s by Dr. Joseph Weizenbaum. The application to the catechism is novel, and a staple of SciFi themes. Take a technology that exists, apply it to an area where it had never existsed before and BAM! An excellent example of this is Arthur C. Clarke's Nine Billion Names for God, in which a computer is placed to a Buddhist temple's long-standing task of recording all the possible names for God.

And A Computer Simulation of God compares favorably with Clarke's work. It is a strong call for reason and faith to interact, and how each can provide solace. That is not exactly the message of the piece, but it hit me in that way. I've studied religion, have a degree in Comparative Religion, and I can see that we look towards mysteries for our comfort. Computers are a form of mystery, or at least they were in the 1960s, and I can understand how the unquestionable logic of the machine when seen in contrast of what the rest of the world presents, could provide the ultimate form of solace for one walking through the valleys of pain.

The script is a touch stagey, though a staged reading lends itself to the delivery of material in a stagey way. The actors read with wonderful emotion and came through with the messages of the script underlined very well indeed. The material presented, which I felt an easy connection and appreciation for, is well-researched and the accuracy of the era is remarkable, but the emotional content is just as accurate, and that is every bit as important.

Perhaps there is a force that draws like minds towards material that goes deep into their soul unconsciously. There is no other person I can think of who had as many points of contact, both concrete and conceptual, with the material that is found in A Computer Simulation of God. On the other hand, even without that connection, it is a remarkable piece of writing. It has won acclaim in screenwriting competitions, understandably, and is currently being produced for the screen by Smokey Pictures. When it finally makes its way to the screen, see it. It will raise questions and entertain, and ultimately that is the outcome of the best films.

Twenty Million People - Reviewed by Christopher J Garcia

Twenty Million People by Christopher J Garcia

A film opens with a screening of a romantic comedy that even Penny Marshall would say was sacherine. After that, the main character says that it was a shitty film, and dissects the ridiculousness of the plot, and especially of the ending. It's the kind of film that telegraphs what's going to happen by giving us the kind of character who is constantly denying that the way those two characters act is how he will ever be.

Yes, it's the classic 'No Way I'll Ever Shoot You With This Gun' concept.

Twenty Million People is a fun film, with a concept comedic tone that delivers laughs at a maximum interval of every couple of minutes. The reason for that is pretty simple: the script is funny and the actors work with drone-strike precision. Brian, played by director/writer Michael Ferrell, is so incredibly smarming (charming smarmy), that it feels like hanging out with my good friends. He's charming, and funny, with exceptional timing and delivery. He's a filmmaker, which naturally makes him more and more caustic in his view of the world. Ashley, played by the lovely Devin Sanchez, is funny, adorable, sarcastic, and just a bit jaded, which she plays underneath a veneer of comedy. She's a stand-up, and a pretty good one. The two meet at the shitty romantic comedy movie night at the coffeehouse where Brian works, and they fall fast and hard, spend two weeks together, and then she disappears.

That's when Brian goes all stalkerocity, then goes completely Nora Ephron and is desperate to not only reconnect with Ashley, but to win her back. She's not so sure, because while she was also playing it like she wanted nothing more than the sex and fun, she left because of his constant reminders that he didn't want a relationship. She was playing along, and while she seemed to be perfectly happy with the arrangement, at least to Brian's face, she was secretly hoping for more.

And so, it seems, was Brian.

This all reminded me of the recent music video hit by Amanda Palmer The Bed Song, a music story of how a couple stop communicating over time and things grow stale. Now, it seems that Ashley was in a relationship that had reached that point, and she's also tired of dating a pot-addled slacker. Brian is terrified of that moment happening to him, but even worse, he's scared of coming to the point where there is no need for talking. He's scared of the comfort, the comfort that can completely turn into complacency so easily, and never seems to in those romantic comedies that Brian so detests. Brian may actually understand that far better than anyone else. At least he understands the path that many relationships take.

And that scares him.

The funny thing is that his path, his journey, is that it's as ridiculous as the films that he rails against. The fact that he'd meet the woman of his dreams, then let her slip away like that just doesn't happen. Yes, people who are deep into each other may just slip away, but never without a whimper, always with a scream. He rails against Romantic Comedies because they end where it should start; at the point where the relationship is just beginning and before it's turned into that The Bed Song world. It's the easy part, sort of, where you're still learning what's what about each other and filling the gaps in the conversation with sex, dinners out, and laughing at each others' little strangenesses.

And there's the couple at the start, Edward and Caroline. They're madly in love, and have certainly reached that The Bed Song phase. In fact, we first see them in a private capacity where they're in bed, and Edward is fully in the depths of his Nintendo DS. Caroline is hoping to get back to her family in St. Louis, and Edward, played by Chris Prine, who is emotionally stupid. I mean, if Brian is a cynic about the process of falling in love, Edward just doesn't understand the entire situation of how things work in the world of love. Of course, almost as soon as we've met them, they're broken up, and we get to see Edward successfully deal with what Brian can not seem to make happen: getting over it. Brian is terrible at it, at dealing with the world he's built, and when he does finally get around to figuring himself out, it requires a turn that is only enabled by the application of those two characters from the film they watch at the beginning - Future Perfect.

And there's a bit of the problem. It's not until 25 minutes in that there are any unrealistic elements, in this case the application of hallucinations of those two characters from the film that led to Brian and Ashley meeting. They both have the same hallucinations, which is as unbelieveable as the entire film those characters come from. It's an awesome application of the concept. They give in to the structure of Romantic Comedy, which allows them to come around and find each other.

If I have one significant quibble, it's the presence of Caroline's Christian roommate. She's well-played, and cute as hell, but the way she's treated in the script, as the nutter Christian, isn't exactly smart. I'm not one who thinks you can't poke fun at Christians (or Muslims, or Jews, or Rastafarians… wait, don't poke fun at Rastafarians), but if you're going to include a character in your film that is pointedly one religion or another, make it mean something to the story. Yes, she plays an important part, she's the catalyst to Edward's recovering from Caroline, but the detail of her religious slant does nothing to advance the story, or really her character.

So, I seriously enjoyed Twenty Million People, and it gave me a chance to reflect on how Brian would have thought about the various romantic comedies of Cinequest. I really think he'd have enjoyed Must Have Been Love, and One Small Hitch probably would have turned him off. Then again, maybe not.

And in the end, is there any other ending that would have satisfied an audience that, despite what we may claim on our OKCupid profiles, is DYING for less realism than the world around us provides?

A film opens with a screening of a romantic comedy that even Penny Marshall would say was sacherine. After that, the main character says that it was a shitty film, and dissects the ridiculousness of the plot, and especially of the ending. It's the kind of film that telegraphs what's going to happen by giving us the kind of character who is constantly denying that the way those two characters act is how he will ever be.

Yes, it's the classic 'No Way I'll Ever Shoot You With This Gun' concept.

Twenty Million People is a fun film, with a concept comedic tone that delivers laughs at a maximum interval of every couple of minutes. The reason for that is pretty simple: the script is funny and the actors work with drone-strike precision. Brian, played by director/writer Michael Ferrell, is so incredibly smarming (charming smarmy), that it feels like hanging out with my good friends. He's charming, and funny, with exceptional timing and delivery. He's a filmmaker, which naturally makes him more and more caustic in his view of the world. Ashley, played by the lovely Devin Sanchez, is funny, adorable, sarcastic, and just a bit jaded, which she plays underneath a veneer of comedy. She's a stand-up, and a pretty good one. The two meet at the shitty romantic comedy movie night at the coffeehouse where Brian works, and they fall fast and hard, spend two weeks together, and then she disappears.

That's when Brian goes all stalkerocity, then goes completely Nora Ephron and is desperate to not only reconnect with Ashley, but to win her back. She's not so sure, because while she was also playing it like she wanted nothing more than the sex and fun, she left because of his constant reminders that he didn't want a relationship. She was playing along, and while she seemed to be perfectly happy with the arrangement, at least to Brian's face, she was secretly hoping for more.

And so, it seems, was Brian.

This all reminded me of the recent music video hit by Amanda Palmer The Bed Song, a music story of how a couple stop communicating over time and things grow stale. Now, it seems that Ashley was in a relationship that had reached that point, and she's also tired of dating a pot-addled slacker. Brian is terrified of that moment happening to him, but even worse, he's scared of coming to the point where there is no need for talking. He's scared of the comfort, the comfort that can completely turn into complacency so easily, and never seems to in those romantic comedies that Brian so detests. Brian may actually understand that far better than anyone else. At least he understands the path that many relationships take.

And that scares him.

The funny thing is that his path, his journey, is that it's as ridiculous as the films that he rails against. The fact that he'd meet the woman of his dreams, then let her slip away like that just doesn't happen. Yes, people who are deep into each other may just slip away, but never without a whimper, always with a scream. He rails against Romantic Comedies because they end where it should start; at the point where the relationship is just beginning and before it's turned into that The Bed Song world. It's the easy part, sort of, where you're still learning what's what about each other and filling the gaps in the conversation with sex, dinners out, and laughing at each others' little strangenesses.

And there's the couple at the start, Edward and Caroline. They're madly in love, and have certainly reached that The Bed Song phase. In fact, we first see them in a private capacity where they're in bed, and Edward is fully in the depths of his Nintendo DS. Caroline is hoping to get back to her family in St. Louis, and Edward, played by Chris Prine, who is emotionally stupid. I mean, if Brian is a cynic about the process of falling in love, Edward just doesn't understand the entire situation of how things work in the world of love. Of course, almost as soon as we've met them, they're broken up, and we get to see Edward successfully deal with what Brian can not seem to make happen: getting over it. Brian is terrible at it, at dealing with the world he's built, and when he does finally get around to figuring himself out, it requires a turn that is only enabled by the application of those two characters from the film they watch at the beginning - Future Perfect.

And there's a bit of the problem. It's not until 25 minutes in that there are any unrealistic elements, in this case the application of hallucinations of those two characters from the film that led to Brian and Ashley meeting. They both have the same hallucinations, which is as unbelieveable as the entire film those characters come from. It's an awesome application of the concept. They give in to the structure of Romantic Comedy, which allows them to come around and find each other.

If I have one significant quibble, it's the presence of Caroline's Christian roommate. She's well-played, and cute as hell, but the way she's treated in the script, as the nutter Christian, isn't exactly smart. I'm not one who thinks you can't poke fun at Christians (or Muslims, or Jews, or Rastafarians… wait, don't poke fun at Rastafarians), but if you're going to include a character in your film that is pointedly one religion or another, make it mean something to the story. Yes, she plays an important part, she's the catalyst to Edward's recovering from Caroline, but the detail of her religious slant does nothing to advance the story, or really her character.

So, I seriously enjoyed Twenty Million People, and it gave me a chance to reflect on how Brian would have thought about the various romantic comedies of Cinequest. I really think he'd have enjoyed Must Have Been Love, and One Small Hitch probably would have turned him off. Then again, maybe not.

And in the end, is there any other ending that would have satisfied an audience that, despite what we may claim on our OKCupid profiles, is DYING for less realism than the world around us provides?

LIFELESS: #beingkindadeadsortasucks by VP Boyle Reviewed by Chris Garcia

Musicals are a crazy, crazy thing right now. We've had a bunch of musicals cross our desk, and some of them are hilariously awesome. Others, not so much. LIFELESS: #beingkindadeadsortasucks is one of the better ones.